Your basket is currently empty!

Teach Translate Travel Repeat

Teaching, translating and travelling around the world one day at a time!

The Grammar of Scientific English: Verbs, Voices and Abbreviations/Acronyms

If you think you have graduated from spacing, numbers and hyphens, try this post on for size! How do you feel about verbs/voices, abbreviations/acronyms and Latin? Now we are getting into the hard parts!

Verbs/Voices – Active and Passive

When someone refers to the ‘voice’ of a verb, they are talking about whether the verb is in the active or passive voice. But what do these really mean? The main difference is the focus of the sentence. In an active voice, a subject does something to an object. In a passive sentence, what is done has importance and the subject is either inconsequential or given but not important. Let’s look at the following two sentences:

The club was established in 1994. Harry founded the club.

The first sentence is a passive one. It follows the structure ‘to be (conjugated) + past participle’; the helping verb ‘to be’ changes to match the subject or object and the verb ‘establish’ changes to the form the perfect and passive tenses. In this case it is the form ‘founded’. ‘The club’ is the object of the verb and the sentence has no subject.

The second sentence is an active one. It has a subject, ‘Harry’, which performs an action, ‘founded’, on an object, ‘the club’. Sentences in English usually are in the active voice and the passive voice often is either too complex or sounds too formal and stuffy.

But what does this have to do with Scientific English? Scientific English often uses the passive voice because what was researched and what was found is more important than who did the research or finding. Furthermore, anyone should be able to do the research and come up with the same results and the same findings, which is at odds with the active voice; this is why we often use the passive voice. The amount we use it depends on the style guide of the publication of your piece of writing, the context of the use of Scientific English (spoken English uses active voice rather than passive voice in most situations), and your own/your professor’s personal style. Some people hate it, some people love it, so make sure to figure out which voice you should be using.

A note about active and passive: scientific language should be clear, concise, and logical. If writing in one voice makes the sentence extremely long but the other shortens it considerably and means the same thing, go with the other voice. Make sure you don’t over-use one voice or the other. Unless directed otherwise (for example, by a style guide), I recommend a good balance of both.

A Myriad of Tenses

So you have figured out how active or passive you should be, but in what tense should you write? Present, past, future? Well, it really depends on which section of a paper you are writing or what you are presenting? But first, we need to think about how English uses tenses?

When we are talking about a single point in time, English uses the simple aspect, whether that be in past, present, or future. What is the present? It is the simplest of all of the aspects: you conjugate the main verb that you have into the tense that you want. The simple present of ‘find’ is ‘find’, past simple is ‘found’ and future simple is either ‘will find’ or ‘going to find’ (depending on how you consider the future if it even exists in English!). English also uses simple aspects to talk about general states: present simple for now, past simple for in the past, future simple for the future. Simple, right?

When introducing a topic and its current general state in a paper or a conference, for example, we use the present. It is what is currently relevant and happening in the field. When you move on to your own specific research, what you did (methods, protocol, procedure), and the results (what was obtained), you should use the past. For example, ‘we mixed chemical A with chemical B, the combination of which turned pink’. This is because the event is already over and does not have an active influence on events in the present (in that case, we would use the present perfect e.g. ‘have measured’).

The discussion section of your paper or talk, where you discuss the implications of your research and results, can have a mix of past, present and future tense as needed. ‘This was done. This was the result. We think it means this. This other thing needs to be done in the future.’

Note: The aforementioned sections are for the natural sciences. Social sciences have a somewhat different writing style; generally, social science articles discuss the results and discussion sections together. Social sciences are less clear-cut and much more muddy and convoluted; you can write the results/discussion section in all three tenses.

|

| Then again, maybe you can if you do research on this! |

Acronyms and Abbreviations

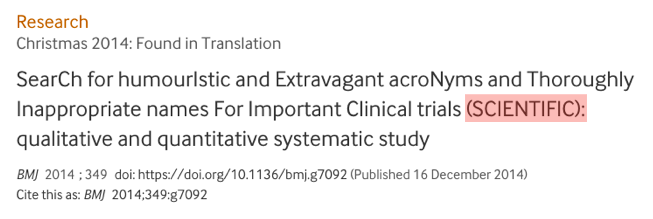

Doing alright so far? Let’s move to an easier topic: abbreviations and acronyms. In Science, an abbreviation is the shortening of a word or phrase (e.g. Dr. for doctor) and an acronym is an abbreviation using the first letters of the constituent words (e.g. US for United States). Science loves using abbreviations and acronyms, but you can’t use them for everything and you can’t just make up your own because it would be easier for you.

While there are many criteria and methods of making acronyms and abbreviations, the general rules are as follows:

- Don’t abbreviate unless necessary

- Don’t abbreviate single worlds (except chemicals, which have their standard abbreviations)

- Use abbreviations more than 3 times or don’t use them at all

- Don’t make up non-standard abbreviations

- Use the abbreviation every time after defining it, then always use it

- Adenosine triphosphate (ATP). …uses ATP. ATP is fundamental for… without ATP.

- Check all abbreviations twice! Are you only 99.9999% sure? Check again!

- Follow the rules the journal style guide sets out

- Sometimes it saves you time because you don’t need to define them!

In other words, do what science does and build off what others have done in the past. Only if something is completely new can you ‘do your own thing’. If so, congrats on being the mother or father of that field (and since there are very few of those in science, think long and hard about it before you go making up random acronyms and abbreviations). That’s all for this post, but stay tuned for the next one. It is about when and how to use Latin in Scientific English!

Click here to find more posts about Scientific English.

Want to follow our social media? Visit Instagram for daily travel posts.

Interested in learning more about Scientific English? You can read a brief post on the History and Use of Scientific English here. More posts on Scientific English are available on the Scientific English page.